BEGINNINGS by Gary Orfield: How the Civil Rights Project Began

Revisit what co-founders Gary Orfield and Chris Edley set out to accomplish by creating the Harvard Civil Rights Project.

The Civil Rights Project really began in the Spring of 1996 at a session I was doing for the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s higher education program. Part of the talk I gave was about the decisions to end affirmative action in California and Texas. I was saying to Jim Honan, who organized the session, “We really ought to get together the leaders of American higher education and make a plan to intervene in the upcoming Supreme Court decision on affirmative action.” And Jim said back, “We can do that.”

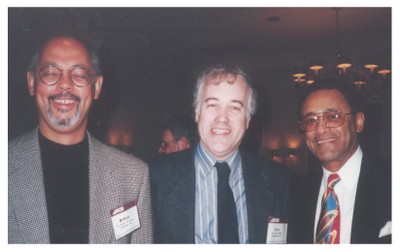

So I enlisted my friend, Chris Edley, a professor at the Harvard Law School at that time, who was doing affirmative action work at the White House for President Clinton. Chris and I drafted a letter to college presidents, civil rights leaders, and leading researchers in the country that invited them to Harvard for an emergency meeting to strategize what we were going to do about the imminent threat against affirmative action. We really didn’t know who would come to this meeting, since it was just shortly before commencement time in the Spring of 1996, and many college presidents have a lot to do around that time of course. Every summer at Harvard, the educational leadership office trains the new presidents of colleges, so they have an incredible network of educational leaders. The staff at Harvard knew exactly how to craft letters to college presidents. I remember one of the funniest parts of the letter said, “Please respond immediately because there’s only a limited number of presidential level suites in Boston hotels.”

On the day of the meeting, 25 college presidents came from major universities, some from the top universities in the country. Directors of federal civil rights agencies and leading researchers were also there. At this “off the record” meeting in the basement of Gutman Library at the Harvard Ed School, we all talked about what could be done. We soon saw that, until this meeting, civil rights enforcement officials, lawyers and researchers hadn’t talked to each other to share information, and nobody had a plan about what to do going forward. By the end of the day, we came to several very important realizations. College leaders had no “Plan B” if affirmative action fell. Many did not know the rudiments of the law; a large number of private college presidents thought that the Supreme Court decision would not affect them. This, of course, was not the case because the law affected anybody who received federal aid money, including virtually all private colleges in the United States. Researchers didn’t know what was needed to defend affirmative action because they were busy researching other issues, such as the problems minority students have at interracial schools, and not the advantages that everyone gets from these interracial schools. Everyone, including the researchers, simply assumed that interracial schools were favorable, but evidence had not been gathered. We knew that this evidence was going to be the key point in the forthcoming Supreme Court battle.

More than two decades after the Supreme Court just barely upheld affirmative action in Bakke, we came out of that meeting knowing that we lacked basic information about how affirmative action was working in the United States. We needed to bring research about law and civil rights together with research on racial equity. And we knew that Harvard was a good place to do this.

After that, Chris and I talked about what we could do to establish some kind of a center. We met with some faculty colleagues. We really didn’t know how to do it. Chris was shuttling back and forth from Washington at this time, and he made absolutely critical connections for us as we got this center launched. What we found out pretty quickly was exactly what our Harvard colleagues told us, “Civil rights are passé, something that nobody is going be excited about -- and you have to think of a different name.” Of course, we decided this meant that absolutely we should include “civil rights” in our name, since we didn’t think civil rights were obsolete or unnecessary in any way.

Chris made a pitch to the president of the MacArthur foundation, who knew us and agreed to meet with us. MacArthur gave us a small grant to get the project going and operating for the first year or so. With that money, we hired one staff member, sponsored two national conferences, began to commission lots of research and create a network of researchers who would ultimately have a great deal of power.

Our first staff member was Michal Kurlaender [see SPOTLIGHT Q & A], who was a young masters-level graduate student (and who looked even younger than she was) with a tremendous amount of pizzazz and imagination. She didn’t know that things couldn’t be done, so she just figured out a way to do them. Fortunately we made a very good choice in hiring Michal. She organized conferences, she was creative and relentless and got people to do things. She worked out of a tiny closet office, down the hall from my office in the Gutman Library, and that’s where the Civil Rights Project really began to take shape.

We first had a conference on alternatives to affirmative action and, as it turned out, these alternatives were one of two central issues that actually came to the Supreme Court later on. We also had a conference on the spread of school segregation in the country. People were very interested in both conferences and we found out quickly that a great many people, both in the legal and the academic world, were more than willing to help and learn and create new research to illuminate the issues. We realized then that we had the potential for creating something substantial from this very small operation.

Gary Orfield is the co-founder, with Christopher Edley, of the Harvard Civil Rights Project and is currently co-director, with Patricia Gándara, of the Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles at UCLA, where the project moved in 2007. Orfield's central interest has been the development and implementation of social policy, with a focus on the impact of policy on equal opportunity for success in American society.